Wajda sets up dichromatic forces against each other within the context of a postwar Poland, or a transitional state from war to peace, and explores or amplifies the tension for his audience. The title itself, Ashes and Diamonds, suggests the binary structure of this film, set in May 8, 1945, aka, the day after WWII ends. The Diamond is a metaphor for the glimmer of hope, the integrity of Poland, the humanity of even a most vicious character: Maciek--the murderous debonair, through his expression of love with Krystyna. The Ashes suggests the irrevocable damage to both the landscape of Poland and the morality of its people, as seen with the fate of the story’s protagonist. Maciek’s blood against the white sheets rhymes with the red and white Polish flag which reminds the audience of the Polish blood seeping onto the history of the state.

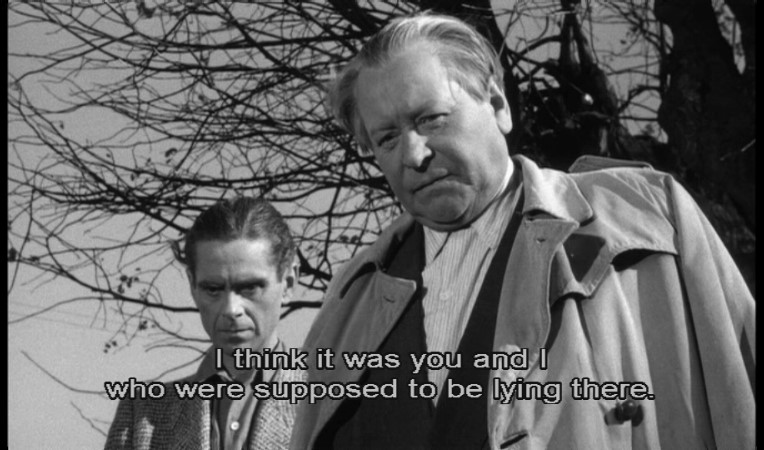

Maciek, the Polish home army soldier, takes the audience through the task of functioning as both an assassin and a lover. The fate of Maciek suggests the constraining reality of WWII on self-renewal through love. The tension between the brutalities of war and idealistic love is amplified by the compression of time. The story itself takes place within a 24 hour period. Maciek kills an innocent Polish man by mistake when ordered to assassinate the incoming commissar, Szczuka. Wajda successfully conveys a sense of bleakness by blurring the distinction between the Polish army and the enemy. Furthermore the sense of bleakness is amplified with the theme of arbitrary annihilation as seen with the murder of the innocent man and the ironic shooting of Maciek which half-suggests, or perhaps questions the possibility of his retribution. The drunken guests leaving the party after sunrise conveys the sense of bleakness because the escape of celebration is met with an abrupt and unprepared reentry into daytime. The bleakness of postwar Poland is punctuated with scenes between Maciak and Krystyna giving the audience a sense of relief but at once fortifying the tension as we return to the political contexts. Most of the outdoor scenes take place when Maciek is with Krystyna.

Wajda uses various theatrical elements to orchestrate the each shot with emotion appropriate to every moment of the film. Trash and ruins is an example of the film's dramatic symbolism. Maciek ends up dieing on a heap of trash which adds another layer to the aftermath or debris of war: the death of the romantic hero perpetuated through propagandistic communist art, which suggests Wajda’s sardonic response to artistic constraints imposed on artists during Communist Poland. Fire is another example. Before the innocent man falls to his death at the doorway of the chappel, large flames rise from his jacket. The fire, as well as death in a doorway, speaks to the irrevocable destruction of war and the transitional period following WWII in Poland.

Ashes and Diamonds mirrors the moral anxiety of Poland just before the 60s as many of the Polish filmmakers conveyed to during this time. Krystyna offers Maciek moral redemption from the murderous life of a member of the underground resistance. However, Maciek’s choice between these two opposing lives; personal needs versus public obligations, individual struggle versus political goals, romantic love versus heroic action, is left ambiguous and ends on a dark note. Like the labyrinth motifs all over the hotel lobby and reflected onto Maciek’s coat as he leaves the hotel, his fate is a complicated path leading to only to a dead end. The ironic display of fireworks at once celebrates the end of the war and illuminate the chilling death of Szczuka, as he falls onto Maciek embracing him. Wajda successfully points out the horrifying essence of war in spite of relative and ephemeral displays of success.

No comments:

Post a Comment